The Endocrine System

The Endocrine System

This lesson introduces the endocrine system and the role it plays in the maintenance of homeostasis.

The following video will provide a review of the Endocrine System.

Functions of the Endocrine System

The endocrine system works with the nervous system to regulate the activities critical to the maintenance of homeostasis. The following are the main functions of the endocrine system:

- Water balance

- Uterine contractions and milk release

- Growth, metabolism, and tissue maturation

- Ion regulation

- Heart rate and blood pressure regulation

- Blood glucose control

- Immune system regulation

- Reproductive functions control

Chemical Signals

Chemical signals, or ligands, are molecules released from one location that move to another location to produce a response. Intracellular chemical signals are produced in one part of a cell, such as the cell membrane, and travel to another part of the same cell and bind to receptors, either in the cytoplasm or in the nucleus. Intercellular chemical signals are released from one cell, are carried in the intercellular fluid, and bind to receptors that are found in other cells, but usually not in all cells of the body.

Intercellular chemical signals can be placed into functional categories on the basis of the tissues from which they are secreted and the tissues they regulate.

- Autocrine chemical signals: These chemical signals are released by cells and have a local effect on the same cell type. Example: prostaglandin-like chemicals that are secreted in response to inflammation.

- Paracrine chemical signals: These chemical signals are released by cells and have effects on other cell types. Example: somatostatin, secreted by the pancreas, inhibits the release of insulin by other cells in the pancreas.

- Neuromodulators and neurotransmitters: These chemical signals are secreted by nerve cells and aid the nervous system. Example: acetylcholine produced during stressful encounters.

- Pheromones: These chemical signals are secreted into the environment and modify the behavior and physiology of other individuals. Example: those produced by women can influence the length of the menstrual cycle of other women.

Receptors

Chemical signals bind to proteins or glycoproteins called receptor molecules to produce a response. The shape and chemical characteristics of each receptor site allow only certain chemical signals to bind to it. This tendency is called specificity.

There are two major types of receptor molecules that respond to an intercellular chemical signal:

- Intracellular receptors: These receptors are located in either the cytoplasm or the nucleus of the cell. Signals diffuse across the cell membrane and bind to the receptor sites on intracellular receptors.

- Membrane-bound receptors: These receptors extend across the cell membrane, with their receptor sites on the outer surface of the cell membrane. They respond to intercellular chemical signals that are large, water-soluble molecules that do not diffuse across the cell membrane.

When an intercellular signal binds to a membrane-bound receptor, three general types of responses are possible:

- Receptors that directly alter membrane permeability: For example, acetylcholine (adrenaline) from nerve fiber endings binds to receptors that are part of the membrane channels for sodium ions.

- Receptors and G proteins: A G proteins (guanine nucleotide-binding proteins) are found on the inner surface of the plasma membrane and function as receptors of hormones. For example, chemical signals include cyclic adenosine monophosphate glycerol and inositol triphosphate that bind to receptor molecules in the cell and alter their activity to produce a response.

- Receptors that alter the activity of enzymes: For example, increasing the activity of an enzyme responsible for the breakdown of glycogen into glucose makes glucose available as an energy source for muscle contractions.

Some intercellular chemical signals diffuse across cell membranes and bind to intracellular receptors. Because these intracellular chemical signals are relatively small and soluble in lipids, they can diffuse through the cell membrane. The chemical signal and the receptor bind to DNA in the nucleus and increase specific messenger RNA synthesis in the nucleus of the cell. The messenger RNA then moves to the ribosomes, then to the cytoplasm, where new proteins are produced.

In contrast, intercellular chemical signals that bind to membrane-bound receptors produce rapid responses. For example, a few intercellular chemical signals can bind to their membrane-bound receptors, and each activated receptor can produce many intracellular chemical signal molecules that rapidly activate many specific enzymes inside the cell. This pattern of response is called the cascade effect.

Hormones

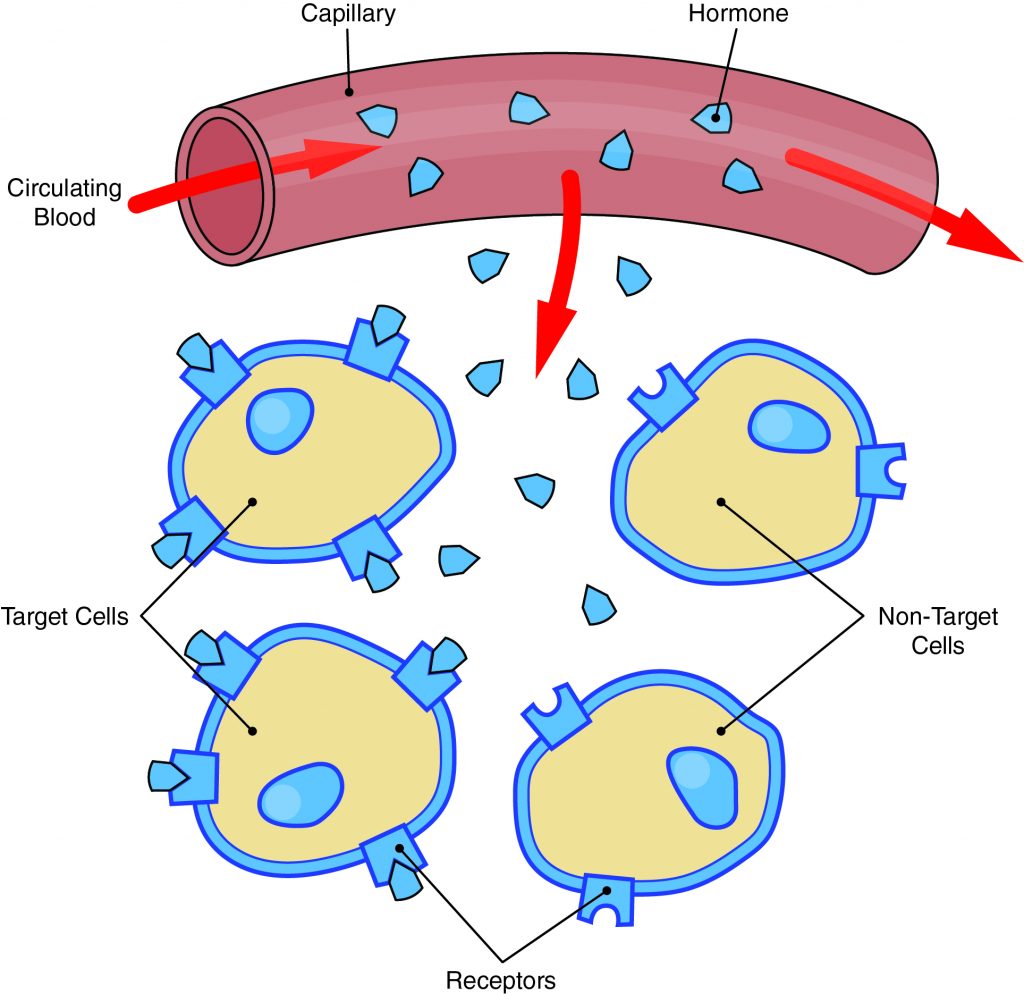

The term endocrine implies that intercellular chemical signals are produced within and secreted from endocrine glands, but the chemical signals have effects at locations that are away from, or separate from, the endocrine glands that secrete them. The intercellular chemical signals, or hormones, are transported in the blood to tissues some distance from the glands. Hormones are produced in minute amounts by a collection of cells to influence the activity of those tissues in a specific way. For example, neurohormones are hormones secreted from cells of the nervous system.

Hormones are distributed in the blood to all parts of the body, but only certain tissues, called target tissues, respond to each type of hormone. Target tissue is made up of cells that have receptor molecules for a specific hormone. Each hormone can only bind to its receptor molecules and cannot influence the function of cells that do not have receptor molecules for the hormone.

Regulation of Hormone Secretion

The secretion of hormones is controlled by negative-feedback mechanisms. Negative-feedback mechanisms keep the body functioning within a narrow range of values consistent with life. Hormone secretion is regulated in three ways:

- Blood levels of chemicals: The secretion of some hormones is directly controlled by the blood levels of certain chemicals. For example, blood glucose levels control insulin secretion.

- Hormones: The secretion of some hormones is controlled by other hormones. For example, hormones from the pituitary gland act on the ovaries and the testes, causing those organs to secrete sex hormones.

- Nervous system: These hormones are controlled by the nervous system. For example, epinephrine is released from the adrenal medulla as a result of nervous system stimulation.

Endocrine Glands and their Secretions

The endocrine system consists of ductless glands that secrete hormones directly into the blood. An extensive network of blood vessels supplies the endocrine glands. The following is a table of hormones secreted by the anterior pituitary gland.

The following is a table of hormones secreted by the anterior pituitary gland.

| Hormone | Target | Response |

| Growth hormone | Most tissues | Increases protein synthesis |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone | Thyroid gland | Increases thyroid hormone secretion |

| Adrenocorticotropic | Adrenal cortex | Increases secretion of cortisol |

| Melanocyte-stimulating hormone | Melanocytes in skin | Increases melanin production to make skin darker |

| Luteinizing hormone | Females: ovaries Males: testes |

Females: promotes ovulation Males: promotes sperm cell production |

| Follicle-stimulating hormone | Females: ovarian follicles Males: seminiferous tubules |

Females: promotes follicle maturation Males: promotes sperm cell production |

| Prolactin | Ovary and mammary glands | Prolongs progesterone secretion |

Additional common hormones are listed in the chart below.

| Gland | Hormone | Target Tissue | Response | Under or Overproduction of Hormone |

| Thyroid Gland | Thyroid hormone | Most cells of the body | Increases metabolic rate | Hypothyroidism Hyperthyroidism |

| Adrenal Medulla | Epinephrine | Heart, blood vessels, liver, adipose cells | Increases cardiac output and blood flow | Addison’s disease |

| Pancreas | Insulin and glucagon | Liver, skeletal muscles, and adipose tissue | Insulin: increases uptake and use of glucose Glucagon: increases breakdown of glycogen |

Diabetes |

The Effects of Aging

The aging process affects hormone activity in one of three ways: their secretion can decrease, remain unchanged, or increase.

In women, the decline in estrogen levels leads to menopause. In men, testosterone levels usually decrease gradually. Decreased levels of growth hormone may lead to decreased muscle mass and strength. Decreased melatonin levels may play an important role in the loss of normal sleep-wake cycles (circadian rhythms) with aging.

Use the following chart as a reference for the production levels of certain hormones within the body throughout the aging process.

Let’s Review

- The endocrine system functions with the nervous system to regulate the many activities critical to the maintenance of homeostasis.

- Chemical signals, or ligands, are molecules released from one location that move to another location to produce a response.

- Chemical signals bind to proteins or glycoproteins called receptor molecules to produce a response.

- A hormone is an intercellular chemical signal that is produced in minute amounts by collections of cells to influence the activity of those tissues in a specific way.

- Hormones are distributed in the blood to all parts of the body, but only certain tissues, called target tissues, respond to each type of hormone.

- Negative-feedback mechanisms control the secretion of hormones.

- The endocrine system consists of ductless glands that secrete hormones directly into the blood.

- The aging process affects hormone activity.

Endocrine System Flashcard Review

You May Subscribe to the online course to gain access to the full lesson content.

If your not ready for a subscription yet, be sure to check out our free practice tests and sample lesson at this link