The Writing Process

TEAS English Review: The Writing Process

Effective writers break the writing task down into steps to tackle one at a time. They allow a certain amount of room for messiness and mistakes in the early stages of writing but attempt to create a polished finished product in the end.

KEEP IN MIND . . .

If your writing process varies from the steps outlined below, that’s okay—as long as you can produce a polished, organized text in the end. Some writers like to write part or all of the first draft before they go back to outline and organize. Others make a plan in the prewriting phase, only to change the plan when they’re drafting. It is not uncommon for writers to compose the body of an essay before the introduction, or to change the thesis statement at the end to make it fit the essay they wrote rather than the one they intended to write.

The point of teaching the writing process is not to force you to follow all the steps in order every time. The point is to give you a sense of the mental tasks involved in creating a well-written text. If you are drafting and something is not working, you will know you can bounce back to the prewriting stage and change your plan. If you are outlining and you end up fleshing out one of your points in complete sentences, you will realize you still need to go back to finish the rest of the plan before you continue drafting.

In other words, it is fine to change the order of steps from the writing process,* or to jump around between them. Published writers do it all the time, and you can too.

* But almost everyone really does benefit from saving the editing until the end.

TEAS English Review: The Writing Process

A writer goes through several discrete steps to transform an idea into a polished text. This series of steps is called the writing process. Individual writers’ processes may vary somewhat, but most writers roughly follow the steps below.

Prewriting is making a plan for writing. Prewriting may include brainstorming, free writing, outlining, or mind mapping. The prewriting process can be messy and include errors. Note that if a writing task requires research, the prewriting process is longer because you need to find, read, and organize source materials.

Writing/Drafting is getting the bulk of the text down on the page in complete sentences. Although most writers find drafting difficult, two things can make it easier: 1) prewriting to make a clear plan, and 2) avoiding perfectionism. Drafting is about moving ideas from the mind to the page, even if they do not sound right or the writer is not sure how to spell a word. For writing tasks that involve research, drafting also involves making notes about where the information came from.

Conferencing is making improvements to the content and structure of a draft. It’s important to get feedback from other people like your peers or someone familiar with the topic being written about. They will provide you with suggestions for how well your writing matches what you intended to write about and what improvements can be made in the next step revising.

Revising may involve moving ideas around, adding information to flesh out a point, removing chunks of text that are redundant or off-topic, and strengthening the thesis statement. Revising may also mean improving readability by altering sentence structure, smoothing transitions, and improving word choice.

Editing is fixing errors in spelling, grammar, and punctuation. Many writers feel the urge to do this throughout the writing process, but it saves time to wait until the end. There is no point perfecting the grammar and spelling in a sentence that is going to get cut later. Peer editing involves switching papers with a classmate or colleague and checking the grammar, spelling, and clarity of each other’s work. Another person may notice a mistake you missed.

Needed Citations

For research projects, you also need to craft citations, or notes that tell readers where you got your information. If you noted this information while working on your prewriting and first draft, all you need to do now is format it correctly. (If you did not make notes as you worked, you will have to search laboriously through all your research materials again.) If you are using MLA or APA styles, citations are included in parentheses at the ends of sentences. If you are using Chicago style, citations appear in footnotes or endnotes.

TEAS English Review: Prewriting Techniques

Prewriting encompasses a wide variety of tasks that happen before you start writing. Many new writers skip or skimp on this step, perhaps because a writer’s prewriting efforts are not clearly visible in the final product. But writers who spend time gathering and organizing information tend to produce more polished work.

Thinking silently is a valid form of prewriting. So is telling someone about what you are planning to write. For very short pieces based on your prior knowledge, it may be enough to use these—but most long writing tasks go better if you also use some or all of the strategies below.

Gathering Information

- Conducting research involves looking for information in books, articles, websites, and other sources. Internet research is almost always necessary, but do not overlook the benefits of a trip to a library, where you can find in-depth printed sources and also get help from research librarians.

- Brainstorming is making a list of short phrases or sentences related to the topic. Brainstorming works best if you literally write down every idea that comes to mind, whether or not you think you can use it. This frees up your mind to find unconscious associations and insights.

- Free writing is writing whatever comes to mind about your topic in sentences and paragraphs. Free writing goes fast and works best if you avoid judging your ideas as you go. Free writing works best if you write quickly and avoid judging your ideas as you go.

- Looping is a series of short free writing sessions that help you find a main topic or focal point for your essay or identify your own stance on an opinion issue. First, complete one short freewriting session of a few minutes, then circle the strongest or most important idea in your writing and begin the next session with a specific focus on that topic.’

Organizing information

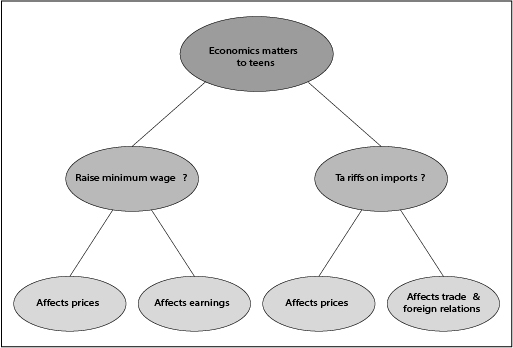

- Mind mapping arranges ideas into an associative structure. Write your topic, main idea, or argument in a circle in the middle of the page. Then draw lines and make additional circles for supporting points and details. You can combine this step with brainstorming to make a big mess of ideas, some of which you later cross out if you decide not to use them. Or you can do this after brainstorming, using the ideas from your brainstormed list to fill in the bubbles.

- Outlining arranges ideas into a linear structure. It starts with an introduction, includes supporting points and details to back them up, and ends with a conclusion. Traditionally, an outline uses Roman numerals for main ideas and letters for minor ideas.

Example:

- Introduction – Economics should be a required subject in high school because it affects political and social issues that matter to students.

- Domestic Issues – Minimum wage

- How do people decide if the minimum wage should be raised?

- They need to know how changes to the minimum wage affect workers, businesses, and prices.

- Foreign Issues – Tariffs

- How do people decide if they favor taxes on imports?

- They need to know how tariffs affect prices and trade.

- Conclusion – These issues affect how much money high school graduates can earn and what they can afford to buy.

TEAS English Review: Paragraph Organization

Paragraphs need to have a clear, coherent organization. Whether you are providing information, arguing a point, or entertaining the reader, the ultimate goal is to make it easy for people to follow your thoughts.

Introductions

The opening of a text must hook the reader’s interest, provide necessary background information on the topic, and state the main point. In an academic essay, all of this typically happens in a single paragraph. For instance, an analytical paper on the theme of unrequited love in a novel might start with a stark statement about love, a few sentences identifying the title and author of the work under discussion, and a thesis statement about the author’s apparently bleak outlook on love.

Body Paragraphs

In informational and persuasive writing, body paragraphs should typically do three things:

- Make a point.

- Illustrate the point with facts, quotations, or examples.

- Explain how this evidence relates to the point.

Body paragraphs need to stay on topic. That is, the point needs to relate clearly to the thesis statement or main idea. For example, in an analytical paper about unrequited love in a novel, each body paragraph should say something different about the author’s bleak outlook on love. Each paragraph might focus on a different character’s struggles with love, presenting evidence in the form of an example or quotation from the story and explaining what it suggests about the author’s outlook. When you present evidence like this, you must introduce it clearly, stating where it came from in the book. Don’t assume readers understand exactly what it has to do with your main point; spell it out for them with a clear explanation.

The structure above is useful in most academic writing situations, but sometimes you need to use other structures:

Chronological – Describe how events happen in order.

Sequential – Present a series of steps.

Descriptive – Describe a topic in a coherent spatial order, e.g. from top to bottom.

Cause/Effect – Present an action and its results.

Compare/Contrast – Describe the similarities and differences between two or more topics.

Conclusions

Like introductions, conclusions have a unique structure. A conclusion restates the thesis and main points in different words and, ideally, adds a bit more. For instance, it may take a broader outlook on the topic, giving readers a sense of why it matters or how the main point affects the world. A text should end with a sentence or two that brings the ideas together and makes the piece feel finished. This can be a question, a quotation, a philosophical statement, an intense image, or a request that readers take action.

If you are asked to improve a paragraph, ask yourself the following questions:

- Can you easily identify the main idea or author’s argument? If not, the paragraph may lack a topic sentence.

- Does the author make several general statements that you find unconvincing? If so, supporting details like anecdotes, examples, historical facts, or scientific studies are needed to back up each statement.

- Do you feel lost or confused when the author changes from one example, argument, or perspective to another? If so, transition words like ‘first,’ ‘on the other hand,’ or ‘in addition’ may clarify the flow of thought.

- Is it unclear what happened first in the narrative or sequence of events? The text may lack time markers like ‘first,’ ‘previously,’ or ‘next’ –or verb tenses like the past perfect (“I HAD DONE my homework before I went to class.”).

- Are there too many main topics or arguments squeezed into one paragraph? If so, the text should be broken down into multiple paragraphs.

Let’s Review!

- The writing process includes prewriting, drafting, revision, and editing.

- For projects that involve research, writers must include the creation of citations within the writing process.

- Effective writers spend time gathering and organizing information during the prewriting stage.

- Writers must organize paragraphs coherently so that readers can follow their thoughts.

You May Subscribe to the online course to gain access to the full lesson content.

If your not ready for a subscription yet, be sure to check out our free practice tests and sample lesson at this link