Tone, Mood, and Transition Words

Tone, Mood, and Transition Words: Why It Matters for the TEAS Exam

The reading section of the TEAS exam requires you to:

- Identify key ideas and details.

- Analyze the structure of texts.

- Interpret the meaning of words and phrases in context.

Mastering tone, mood, and transition words ensures you can approach passages critically, make accurate inferences, and answer comprehension questions confidently. It’s a foundational skill for succeeding on this exam and in nursing, where interpreting written communication is essential. Tone reveals the author’s attitude, such as being serious or persuasive, while mood shows the feeling the text creates, like happiness or suspense. Transition words connect ideas and indicate relationships like cause-and-effect or contrast, making the passage easier to follow. Mastering these skills ensures you can analyze the text, make inferences, and answer comprehension questions with confidence for your upcoming TEAS exam.

TEAS Exam Review: Tone

The tone of a text is the author’s or speaker’s attitude toward the subject. The tone may reflect any feeling or attitude a person can express: happiness, excitement, anger, boredom, or arrogance.

Readers can identify tone primarily by analyzing word choice. The reader should be able to point to specific words and details that help to establish the tone.

Example: The train rolled past miles and miles of cornfields. The fields all looked the same. They swayed the same. They produced the same dull nausea in the pit of my stomach. I’d been sent out to see the world, and so I looked, obediently. What I saw was sameness.

Here, the author is expressing boredom and dissatisfaction. This is clear from the repetition of words like “same” and “sameness.” There’s also a sense of unpleasantness from phrases like “dull nausea” and passivity from words like “obediently.”

Sometimes an author uses an ironic tone. Ironic texts often mean the opposite of what they actually say. To identify irony, you need to rely on your prior experience and common sense to help you identify texts with words and ideas that do not quite match.

Example: With that, the senator dismissed the petty little problem of mass shootings and returned to the really important issue: his approval ratings.

| BE CAREFUL!

When you’re asked to identify the tone of a text, be sure to keep track of whose tone you’re supposed to identify, and which part of the text the question is referencing. The author’s tone can be different from that of the characters in fiction or the people quoted in nonfiction. Example: The reporter walked quickly, panting to catch up to the senator’s entourage. “Senator Biltong,” she said. “Are you going to take action on mass shootings?” “Sure, sure. Soon,” the senator said vaguely. Then he turned to greet a newcomer. “Ah ha! Here’s the man who can fix my approval ratings!” And with that, he returned to the really important issue: his popularity. In the example above, the author’s tone is ironic and angry. But the tone of the senator’s dialogue is different. The line beginning with the words “Sure, sure” has a distracted tone. The line beginning with “Ah ha!” has a pleased tone. |

Here the author flips around the words most people would usually use to discuss mass murder and popularity. By calling a horrific issue “petty” and a trivial issue “important,” the author highlights what she sees as a politician’s backwards priorities. Except for the phrase “mass shootings,” the words here are light and airy—but the tone is ironic and angry.

Literary devices such as simile, metaphor, personification, or allusion may help the author establish the tone of a text.

- A simile is a comparison using comparing words such as “like” or “and.”

EXAMPLE: The moon was like a policeman’s flashlight tracking them as they tried to escape through the woods.

In this example, the simile of the policeman’s flashlight, combined with the verbs “tracking” and “escape,” builds a tense and suspenseful tone.

- A metaphor is a comparison WITHOUT comparing words.

EXAMPLE: The moon was a warm glowing lamp in the window welcoming them home from the dark woods.

In this example, the metaphor of the lamp, along with the adjectives “warm” and “glowing” and the verb “welcoming,” creates a pleasant and comforting tone.

- Personification is when authors attribute human behavior or traits to non-human objects or animals.

EXAMPLE: The moon cheered on the marathon runners as they raced through the woods, leapt boulders, ducked branches, and sprinted towards the finish line.

Here, the moon ‘cheers on’ the runners like an enthusiastic sports fan. Of course the moon cannot actually cheer, but this personification combines with the rapid series of action verbs (“raced,” “leapt,” “ducked,” and “sprinted”) to build momentum and an active, exciting tone.

- Allusion is a reference to a different work (poem, book, TV show, movie…) or something in pop culture or history.

EXAMPLE: The moon reminded her of the Snoopy balloon in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Parade as she skipped through the woods at midnight.

This allusion to a popular cartoon character and cultural event for families sets a playful tone that is reinforced by the verb “skipped.”

These examples show how the same image or setting (the moonlit woods) can change tone – from suspenseful to comforting to exciting to playful – based largely on literary devices and word choice. If you have trouble characterizing the tone of a text, try looking for literary devices.

TEAS Exam Review: Mood

A concept related to tone is mood, or the feelings an author produces in the reader. To determine the mood of a text, a reader can consider setting and theme as well as word choice

and tone. For example, a story set in a haunted house may produce an unsettled or frightened feeling in a reader.

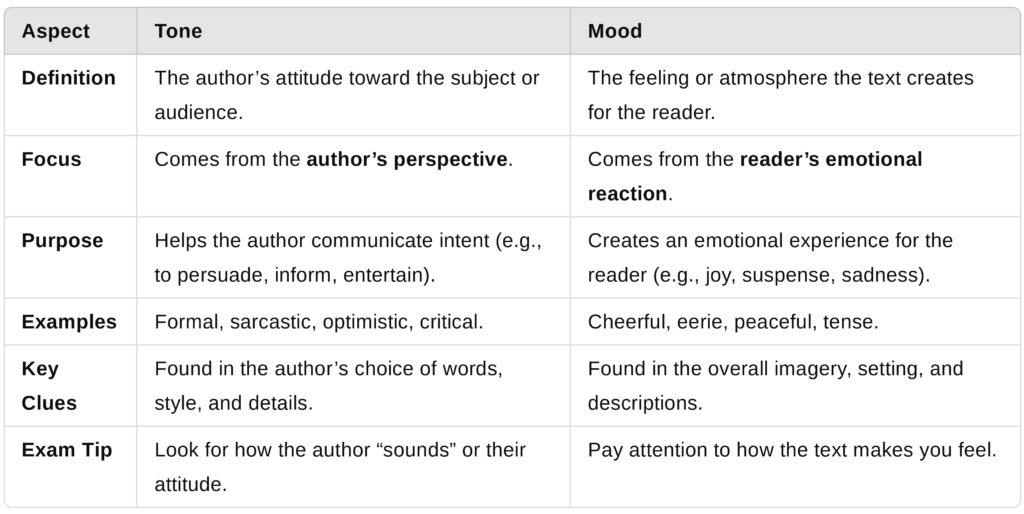

Tone and mood are often confused. This is because they are sometimes the same. For instance, in an op-ed article that describes children starving while food aid lies rotting, the author may use an outraged tone and simultaneously arouse an outraged mood in the reader.

However, tone and mood can be different. When they are, it’s useful to have different words to distinguish between the author’s attitude and the reader’s emotional reaction.

Example: I had to fly out of town at 4 a.m. for my trip to the Bahamas, and my wife didn’t even get out of bed to make me a cup of coffee. I told her to, but she refused just because she’d been up five times with our newborn. I’m only going on vacation for one week, and she’s been off work for a month! She should show me a little consideration.

Here, the tone is indignant. The mood will vary depending on the reader, but it is likely to be unsympathetic.

TEAS Tip: Tone vs. Mood 👀📚 How To Tell The Difference

TEAS Exam Review: Transitions

Authors use connecting words and phrases, or transitions, to link ideas and help readers follow the flow of their thoughts. The number of possible ways to transition between ideas is almost limitless.

Below are a few common transition words, categorized by the way they link ideas.

Transitions may look different depending on their function within the text. Within a paragraph, writers often choose short words or expressions to provide transitions and smooth the flow. Between paragraphs or larger sections of text, transitions are usually longer. They may use some of the key words or ideas above, but the author often goes into detail restating larger concepts and explaining their relationships more thoroughly.

Between Sentences: Students who cheat do not learn what they need to know. As a result, they get farther behind and face greater temptation to cheat in the future.

Between Paragraphs: As a result of the cheating behaviors described above, students find themselves in a vicious cycle.

Longer transitions like the latter example may be useful for keeping the reader clued in to the author’s focus in an extended text. But long transitions should have clear content and function. Some long transitions, such as the very wordy “due to the fact that” take up space without adding more meaning and are considered poor style.

Let’s Review!

- Tone is the author’s or speaker’s attitude toward the subject.

- Literary devices like simile, metaphor, personification, and allusion contribute to tone.

- Mood is the feeling a text creates in the reader.

- Transitions are connecting words and phrases that help readers follow the flow of a writer’s thoughts.

Subscribe to the online course to gain access to the full lesson content.

If your not ready for a subscription yet, be sure to check out our free practice tests and sample lesson at this link